Introduction

Offshore-wind nacelles from Newcastle, photovoltaic (PV) inverters from Cambridge, and hydrogen-electrolyser stacks manufactured in Sheffield are moving from British quaysides to power plants on every continent. International demand for renewable-energy infrastructure is expanding by double digits as governments race to achieve net-zero targets and diversify energy security. Yet the act of shipping a container of wind-turbine hubs or lithium-ion battery packs is governed by a dense lattice of technical standards, trade-finance instruments, export-control rules, and customs declarations.

This article provides a structured, text-rich roadmap—spanning pre-shipment certification to post-export record-keeping—for United Kingdom exporters of renewable-energy equipment. It synthesises authoritative guidance and industry best practice, highlights public-and private-sector finance, and demonstrates how the Customs Declarations UK (CDUK) platform reduces the friction that often arises at the most error-prone stage: lodging electronic declarations on HMRC’s Customs Declaration Service (CDS).

1 – Understanding International Compliance Frameworks

1.1 IEC and ISO Standardisation

The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) publishes consensus-based standards that cover virtually every component shipped in a solar, wind, or hydro project. IEC 61215 and 61730 apply to crystalline-silicon PV modules; IEC 61400 governs wind-turbine design and safety; IEC 62933 addresses stationary energy-storage systems. Conformity is demonstrated through the IECRE certification system, a globally recognised passport that reduces duplicate testing and accelerates market entry.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) complements IEC rules: ISO 14001 underpins environmental-management systems, while ISO 50001 sets energy-management benchmarks for factory production lines. Manufacturers and exporters should embed these frameworks into quality-assurance programmes to simplify technical due-diligence by overseas buyers.

1.2 CE and UKCA Marking

Products destined for the European Economic Area must carry the CE mark, signalling compliance with EU directives on safety, electromagnetic compatibility, and hazardous substances. Post-Brexit, Great Britain recognises the UKCA mark for domestic placements; however, many firms maintain dual marking to reassure non-EU buyers who treat the CE mark as shorthand for quality.

1.3 Export Controls and Dual-Use Screening

Most renewable-energy hardware is uncontrolled, but advanced power electronics, wide-bandgap semiconductors, or grid-management software may be classified as dual-use under the Export Control Order 2008. Consult the Strategic Export Control Lists and, where uncertainty persists, request guidance from the Export Control Joint Unit. Failure to obtain a licence can trigger shipment seizures and criminal penalties.

2 – Financing the Green Export: Public and Private Options

The capital intensity of renewable projects often threatens to outstrip internal cash flows, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises. UK Export Finance (UKEF) bridges that gap with a suite of facilities:

- Direct Lending Facility—government loans up to £200 million to overseas customers purchasing UK-origin equipment.

- Buyer Credit and Supplier Credit Guarantees—up to 80 per cent cover for banks financing renewable contracts above £1 million.

- Export Development Guarantee—support for long-term corporate borrowing in excess of £25 million to scale production lines dedicated to export markets.

UKEF backed more than £500 million in British offshore-wind exports to Taiwan between 2019 and 2023, demonstrating the agency’s appetite for green-infrastructure deals. Private asset-finance houses and green-bond issuances provide additional liquidity, while multilateral climate-finance programmes—from the World Bank’s Scaling Solar initiative to the African Development Bank’s Desert to Power plan—create demand-side certainty.

3 – Customs Infrastructure: From EORI to Commodity Code

An exporter’s compliance journey begins with an Economic Operator Registration and Identification (EORI) number prefixed “GB” (or “XI” when Northern-Ireland routing is involved). The EORI appears on every contract and on the electronic export declaration lodged through CDS.

Correct commodity classification is decisive: crystalline-silicon PV modules typically fall under HS 8541 40, complete wind turbines under 8502 31, and lithium-ion battery packs under 8507 60. The chosen ten-digit UK Global Tariff code drives any import-country duty rate, licence trigger, or documentary waiver. Misclassification can result in duty disputes lasting up to three years.

The Customs Procedure Code (CPC) signals the regime; a straightforward permanent export is coded 10 00 001. Indirect ex-works sales or temporary exports for demonstration may invoke different CPC suffixes.

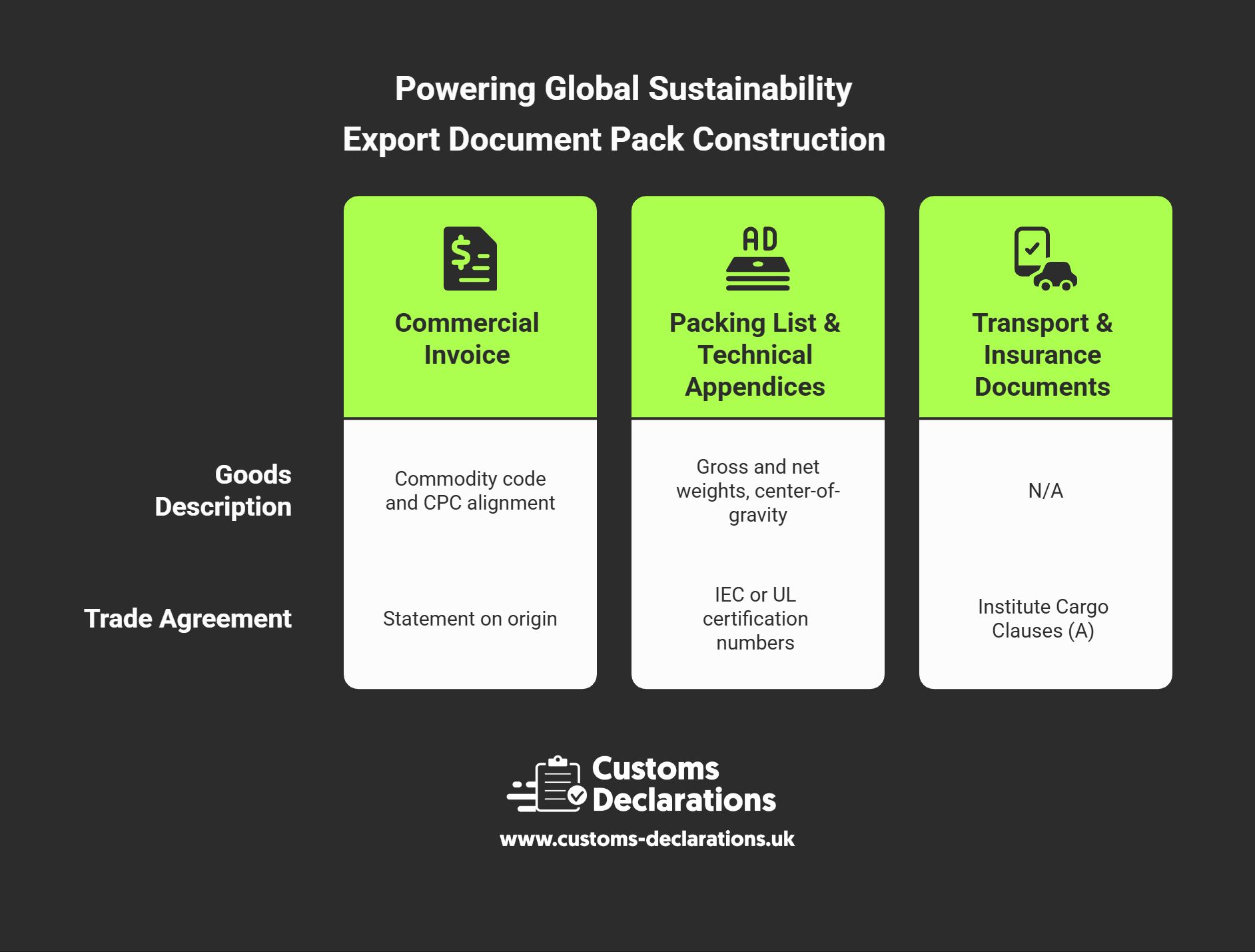

4 – Constructing the Export Document Pack

4.1 Commercial Invoice

The invoice must align exactly with the commodity code and CPC declared: include an intelligible goods description (“IEC 61215 certified monofacial PV panels”), Incoterm®, EORI number, and—where a trade agreement applies—a statement on origin. Under the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement, exporters can self-certify origin, obviating the need for a EUR1 certificate below €6000 or where “Approved Exporter” status exists.¹

4.2 Packing List and Technical Appendices

Large nacelles and blades often travel as break-bulk; the packing list should record gross and net weights, centre-of-gravity points, and lifting lugs to satisfy port-authority handling rules. Attach data sheets that reference IEC or UL certification numbers—many customs authorities accept PDFs if they bear a digital signature.

4.3 Transport and Insurance Documents

Bills of Lading, Sea Waybills, or Air Waybills populate the transport column in CDS, while an Institute Cargo Clauses (A) insurance certificate demonstrates coverage against all risks, a frequent buyer condition for project-finance disbursement.

5 – Electronic Export Declarations via Customs Declarations UK

Submitting a compliant declaration to CDS is often the critical-path item in a project schedule. The CDUK platform transforms technical CDS data elements into plain English:

- Select Export Type – choose “Full Export Declaration”.

- Enter Commodity Lines – input HS code, quantity (statistical units such as Watts for solar or number of turbines for wind), and ex-works value.

- Reference Licences or Certificates – if a dual-use licence applies, quote the licence number and attach a PDF.

- CPC and Preference Indicator – for UK-EU shipments, enter preference code “U” and attach the origin statement; CDUK validates syntax automatically.

- Validate & Submit – real-time checks flag inconsistencies, such as a solar panel declared in kilograms instead of Watts. On acceptance, HMRC issues a Movement Reference Number (MRN) within seconds.

A deep-sea container must lodge its declaration at least 24 hours before vessel loading, whereas short-sea or Ro-Ro traffic requires a two-hour window.

Further guidance on export declarations and cds declarations is available on the CDUK knowledge base

6 – Destination-Market Formalities and Trade-Agreement Leverage

Many import-country customs administrations grant duty-free status to renewable-energy equipment to promote Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. Examples include Vietnam’s exemption for solar modules and Mexico’s zero duty on wind-turbine components. Validate eligibility with the buyer’s customs broker before incoterms are fixed; if proof of origin is required, ensure the EUR1 or invoice statement accompanies the shipment.

7 – Mitigating Risk Through Incoterms and Insurance Clauses

Selecting an Incoterm® that balances control and risk is fundamental. CIF (Cost, Insurance and Freight) places carriage risk on the seller until goods pass the ship’s rail; DAP (Delivered at Place) may be preferable when exporters bundle installation services. Ensure that marine-cargo insurance deductibles do not exceed the damage-free threshold under project-finance loan covenants.

8 – Post-Export Obligations: Record Retention and After-Sales Support

HMRC mandates retention of all customs records, MRNs, and commercial documents for six years; IEC certificates and test reports should be archived for the full warranty period (often 20–25 years for PV modules). Equip in-country technicians with up-to-date maintenance manuals and firmware patches to survive random post-clearance audit by destination authorities evaluating performance or safety compliance.

Conclusion

Exporting renewable-energy equipment from the United Kingdom is both a commercial imperative and a moral contribution to global decarbonisation. Success, however, depends on disciplined adherence to IEC and ISO standards, proactive engagement with export-finance instruments, and mastery of the customs declaration process. By integrating these strands within a single workflow—anchored by the Customs Declarations UK platform—British manufacturers and EPC contractors can deliver high-value, zero-carbon technology to the world’s fastest-growing energy markets on time, on budget, and in full regulatory compliance.