Introduction

Importing a Japanese Domestic Market (JDM) vehicle into Great Britain is absolutely achievable when you approach it as a single, joined-up process. You will prepare a compliant customs declaration, determine whether you can lawfully claim preferential duty under the UK–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), calculate duty and VAT on a correct customs value, complete HMRC’s NOVA notification, satisfy UK safety and environmental rules—often via Individual Vehicle Approval (IVA)—and then register the vehicle with DVLA. Treating these steps as one workflow eliminates most delays and surprises.

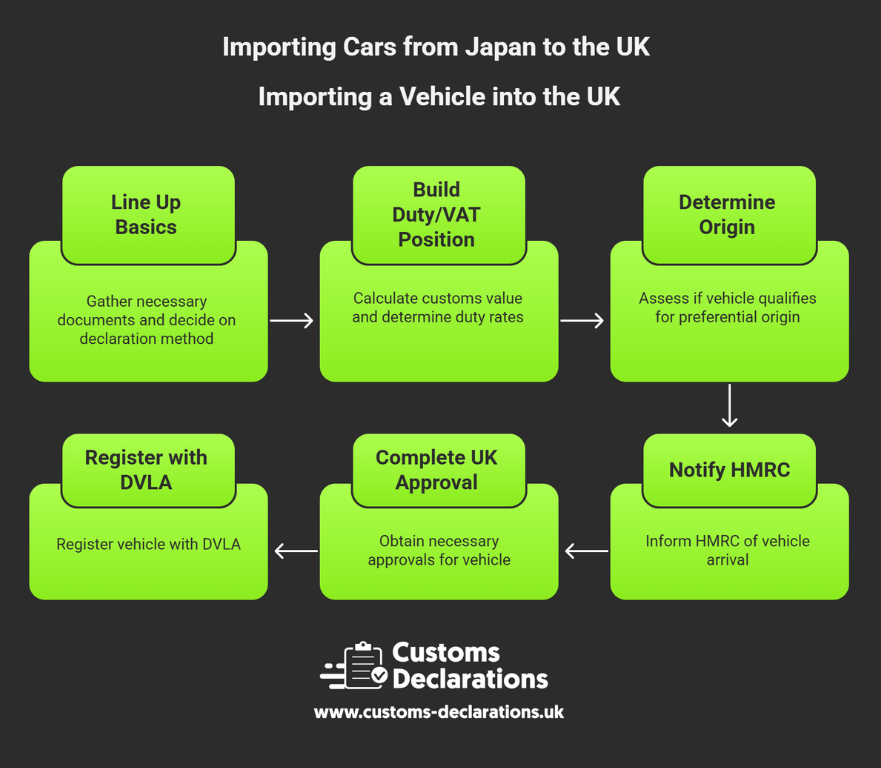

The roadmap in brief

A smooth import follows a logical arc. First, line up the basics: ensure you have a GB EORI, decide who will lodge your import declaration (you, via a platform such as Customs Declarations UK), and assemble your commercial and shipping documents. You will declare the car on HMRC’s Customs Declaration Service (CDS).

Next, build your duty/VAT position: compute the customs value (typically the price paid plus transport and insurance to the UK frontier), determine the duty rate, and calculate import VAT on a duty-inclusive base. If you are VAT-registered, Postponed VAT Accounting (PVA) usually allows you to defer the cash outlay.

Then ask the key question on origin: can you prove the vehicle is of Japanese preferential origin under Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) (commonly giving a 0% rate for qualifying passenger cars) or must you use the Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) rate typically applied to non-originating cars? The answer depends on evidence, not seller location.

After the border entry, notify HMRC through Notification of Vehicle Arrivals (NOVA) within fourteen days so Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) can later register the vehicle, then complete UK approval (type approval or IVA) and proceed to DVLA registration.

Preferential origin under the UK–Japan CEPA: when can you claim it?

A car bought in Japan is not automatically “originating” in Japan for preferential duty. To lawfully claim CEPA preference, the vehicle must meet the product-specific rule of origin (PSR) for its subheading. That manufacturing rule—not the shipping route—determines origin. You may claim preference either on the basis of a Statement on Origin from the exporter, or by Importer’s Knowledge if you truly hold sufficient manufacturing evidence. If origin is not demonstrated, declare at the MFN rate. Keep proofs on file for audit.

Because duty savings can be substantial, obtain the exporter’s Statement on Origin before shipment whenever you intend to claim preference. Always verify the correct subheading’s current preferential rate for Japan in the UK Trade Tariff before you file.

Customs valuation: build the correct base for duty and VAT

HMRC’s default valuation is the transaction value—the price actually paid or payable—plus transport and insurance to the UK border and any other dutiable adjustments per HMRC rules. Exclude UK inland delivery after import and DVLA fees; include only costs to the frontier and those that are conditions of sale. Over- or under-stating the customs value distorts both duty and VAT, creating exposure to additional assessments.

For VAT purposes, remember the base is duty-inclusive: import VAT is calculated on the customs value plus any customs duty and other includable charges. VAT-registered importers commonly use PVA to account for import VAT on the VAT return rather than paying it at the frontier, improving cashflow.

A simple illustration. If your CIF value is £12,000 and MFN duty is 10%, duty = £1,200 and VAT = 20% of £13,200 = £2,640. If you validly claim CEPA preference at 0%, VAT = 20% of £12,000 = £2,400. Replace these with live rates on your filing date.

Classify first, then declare: getting the core data right

Passenger vehicles are declared under Chapter 87 and, for cars, generally under heading 8703, with subheading detail based on propulsion, capacity, or technology (e.g., hybrids, EVs). Accurate classification determines duty rate and any measures; misclassification is a frequent trigger for delay or reassessment. Confirm the final code in the UK Trade Tariff and ensure the description, origin, and valuation story align across your documents and declaration.

On the Customs Declaration Service, a straightforward import typically uses a full import declaration. You will need the commodity code, Customs Procedure Code, customs value, origin, Incoterms, your EORI, and any licence references. Authorised traders may use simplifications, but supplementary obligations still apply.

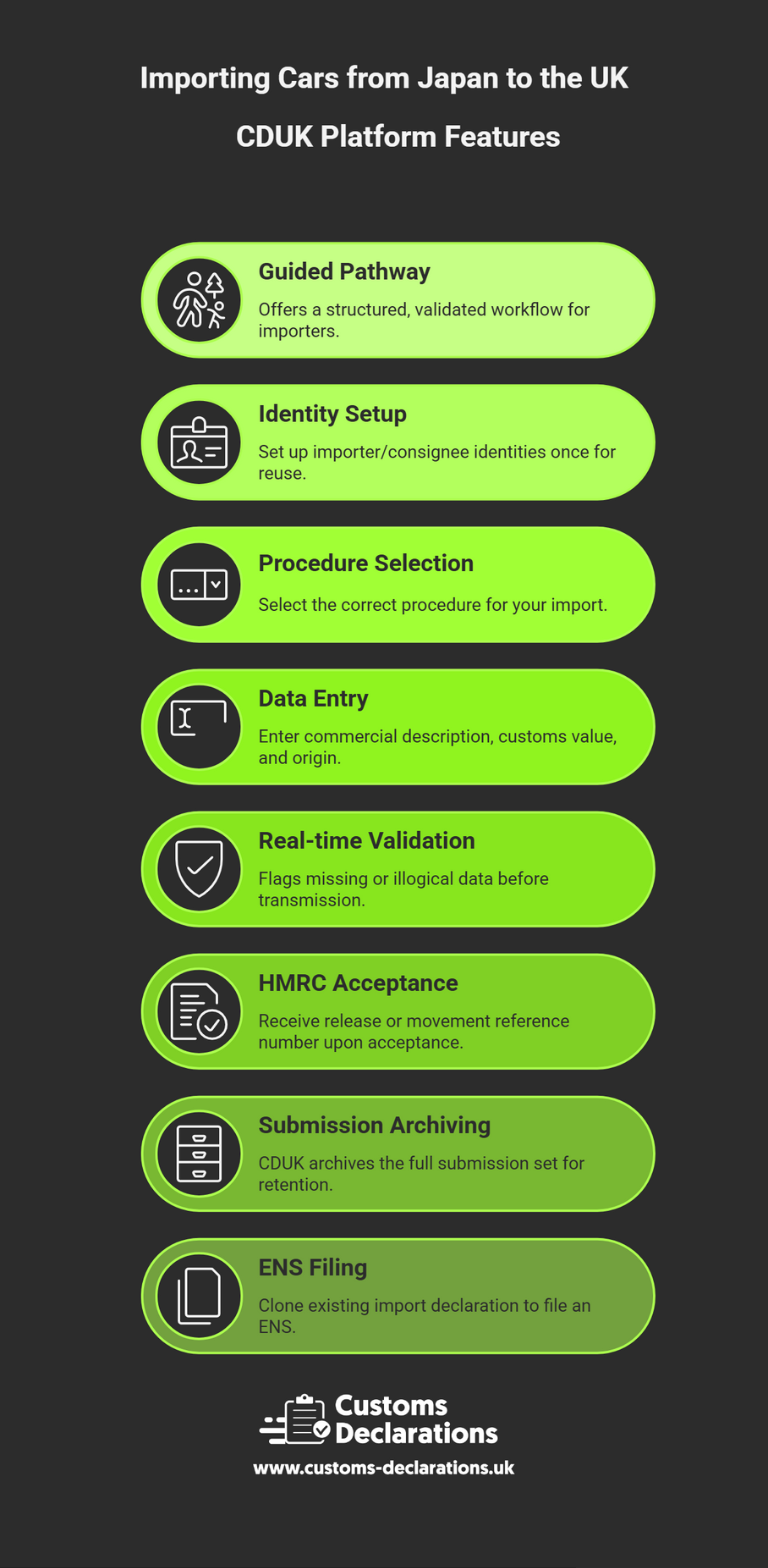

Filing via the Customs Declarations UK (CDUK) platform

The Customs Declarations UK platform offers a guided, plain-English pathway into CDS for importers who prefer a structured, validated workflow. Within CDUK, set up the importer/consignee identities once, reuse clone feature for repeat lanes, and select the correct procedure for your import. Enter the commercial description, your customs value and components, and your origin position. Real-time validation flags missing or illogical data before transmission to CDS. On HMRC acceptance, you receive the release or movement reference number, and CDUK archives the full submission set for statutory retention—which you should pair with your NOVA confirmation and any approval documentation.

CDUK platform also allows you to lodge safety and security filings, you can simply clone the existing import declaration to file an ENS.

NOVA: the non-negotiable notification for vehicle imports

Within 14 days of the vehicle’s arrival, you must notify HMRC through NOVA (Notification of Vehicle Arrivals). NOVA confirms the VAT/duty position and enables DVLA to proceed; there is no registration without NOVA. After NOVA is recorded, allow around 48 hours for DVLA systems to display it before you contact them. Keep your NOVA confirmation with your customs evidence.

Safety and environmental compliance: IVA and common JDM tweaks

Unless your exact model already carries a valid GB/UK(NI) type approval, the usual route is IVA (Individual Vehicle Approval) for a single-vehicle import. Many JDM vehicles require modest modifications to pass: a miles-per-hour or dual-marked speedometer; a compliant rear fog lamp; headlamps that meet GB beam requirements; and evidence that emissions/noise meet standards appropriate to the vehicle’s age and specification. DVSA’s IVA guidance is practical and helps you avoid re-tests; bring any manufacturer letters or export certificates that substantiate equivalence to comparable standards.

Be careful with “blanket exemptions” you may read online—such as claims that “over ten years old” means IVA is never needed. Exemptions are nuanced and depend on category/specification; always test your case against the current DVSA guidance before relying on a shortcut.

DVLA registration: putting the car on the road

Once NOVA is visible to DVLA and your approval evidence is in order, submit your application to DVLA—typically form V55/5 for used imports—include the first registration fee and VED, attach proof of identity/address, insurance, and IVA/MOT as applicable. On approval, DVLA issues your V5C and registration number. Keep a complete copy of the file in your import archive for traceability.

The documents that prove your story

A coherent, consistent file is your best defence against queries. At minimum, retain the commercial invoice, bill of lading, proof of freight/insurance to the UK frontier, any Statement on Origin or importer-knowledge evidence used for CEPA, your accepted CDS declaration and status messages, NOVA confirmation, approval pass (IVA/type approval), and the DVLA registration paperwork. Organise everything by shipment and tie each record to the declaration reference so that quantities, values, and narratives reconcile instantly at audit.

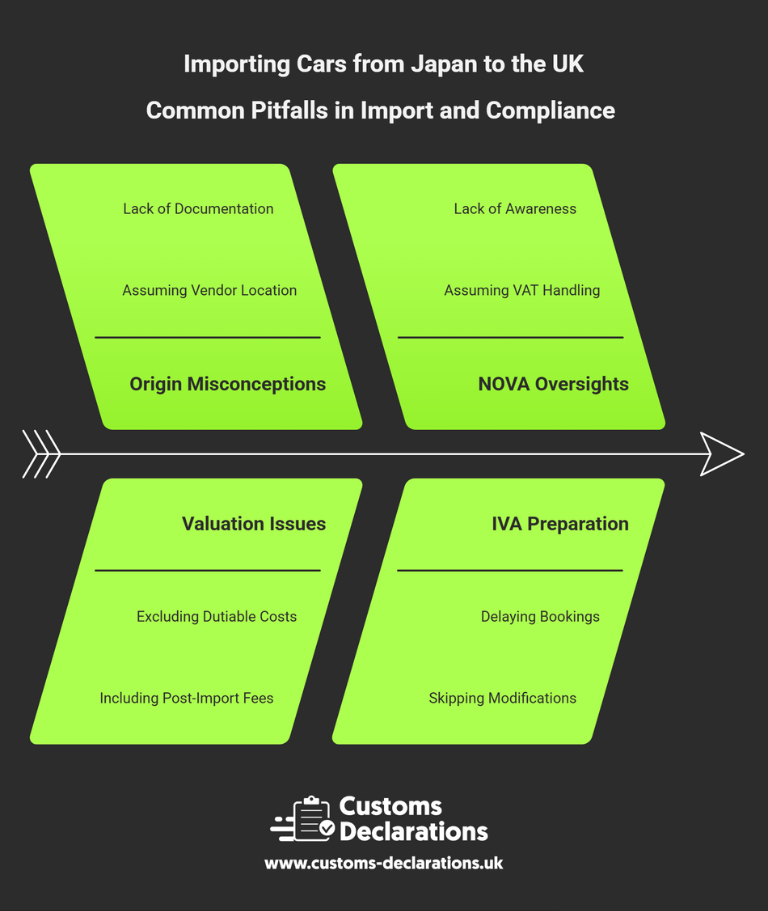

Common pitfalls—and the simple controls that prevent them

Assuming “bought in Japan” means Japanese origin. Preference is about manufacture to the CEPA rule, not the vendor’s location. Do not claim without a Statement on Origin or robust importer-knowledge evidence.

Valuation gaps or over-inclusions. Excluding dutiable costs to the frontier or, conversely, including post-import UK inland delivery/fees will skew your customs value and the VAT that rides on it. Keep a clear calculation sheet.

Skipping NOVA because VAT was handled on entry. NOVA is mandatory. No NOVA, no DVLA registration.

Rushing DVLA before systems sync. Allow roughly forty-eight hours after NOVA is confirmed before contacting DVLA; otherwise you risk a needless back-and-forth.

Under-preparing for IVA. Book early and complete obvious modifications in advance; DVSA’s “how to get a pass” guidance helps you avoid avoidable re-tests.

How Customs Declarations UK underpins the process

Filing accurately, first time, is the key to low-friction imports. Customs Declarations UK supports you by mapping plain-English input fields to CDS data elements, enforcing logic checks before submission, storing your declaration pack for six years, and creating reusable templates for repeat models and lanes. When HMRC accepts your entry, CDUK captures the release/movement reference you will share with your forwarder and file with your NOVA record and approval documents. This single source of truth shortens response times to any HMRC or DVLA queries and makes the lane scalable.

For deeper how-tos and keyword-targeted guidance, see our internal pages: import declarations, cds declarations, and ens declarations. For statutory context and forms, consult GOV.UK’s resources on NOVA, IVA, and registering imported vehicles.

Conclusion

A Japanese car can be imported into the UK smoothly and predictably when you follow an evidence-led sequence: confirm whether CEPA preference applies and secure origin proof; compute a correct customs value; file a clean CDS declaration—ideally via Customs Declarations UK for validation and audit readiness; submit NOVA in fourteen days; pass IVA or present type-approval evidence; and register with DVLA. With disciplined documents and aligned datasets, you will avoid the classic pitfalls and convert imports from one-off projects into a repeatable, well-governed process.