Introduction: A Quiet Policy Shift With Big Consequences

On 2 June 2025 the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) confirmed that the United Kingdom will postpone – in effect, scrap for now – the sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) border checks and fees originally scheduled to apply to most fruit and vegetable shipments arriving from the European Union. The controls, which form part of the government’s Border Target Operating Model (BTOM), had been due to start on 1 July 2025. They will now remain suspended until 31 January 2027 while London and Brussels negotiate a comprehensive UK-EU SPS agreement.

Although framed as a technical “easement”, the decision reshapes £9 billion-a-year in fresh-produce trade, offers estimated annual savings of about £200 million for importers, and feeds directly into the government’s stated ambition to contain food-price inflation. It also signals a strategic shift away from unilateral post-Brexit controls toward a more cooperative and risk-based approach to biosecurity.

Understanding SPS Checks and the BTOM

Sanitary and phytosanitary measures are the inspection, certification and enforcement regimes that guard against pests, animal diseases and food-borne hazards. Within the EU single market these checks occur largely behind the scenes, because member states apply common rules. When the UK left that framework it committed to building its own, staged border system, culminating in the BTOM published in August 2023.

Under the BTOM all agri-food imports are classified as low, medium or high risk. Medium-risk plant products – including staples such as tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, grapes, citrus fruit, peaches, cherries and plums – were earmarked for routine documentary and identity checks, plus physical inspections at border control posts (BCPs). Importers would also pay new plant-health fees of up to £145 per consignment.

A temporary easement introduced in 2021 allowed these consignments to continue entering Great Britain with minimal paperwork. That easement was extended several times as port operators, software suppliers and the horticulture industry argued that infrastructure and staffing were not yet ready. By spring 2025, however, DEFRA had formally confirmed a 1 July “switch-on” date – until this month’s reversal.

What Exactly Has Been Cancelled or Delayed?

- Routine documentary and physical SPS inspections at BCPs for medium-risk EU fruit and vegetables.

- Plant-health certification fees linked to those inspections.

- Advance notification requirements for the same commodities moving through the PEACH or IPAFFS portals.

Other elements of the BTOM stay in force. Meat, dairy, fish, composite products and high-risk plants continue to require export health certificates and, in many cases, veterinary checks. Live plants, certain seeds and seed potatoes – classed as high risk – are not covered by the fresh-produce easement and still attract full controls.

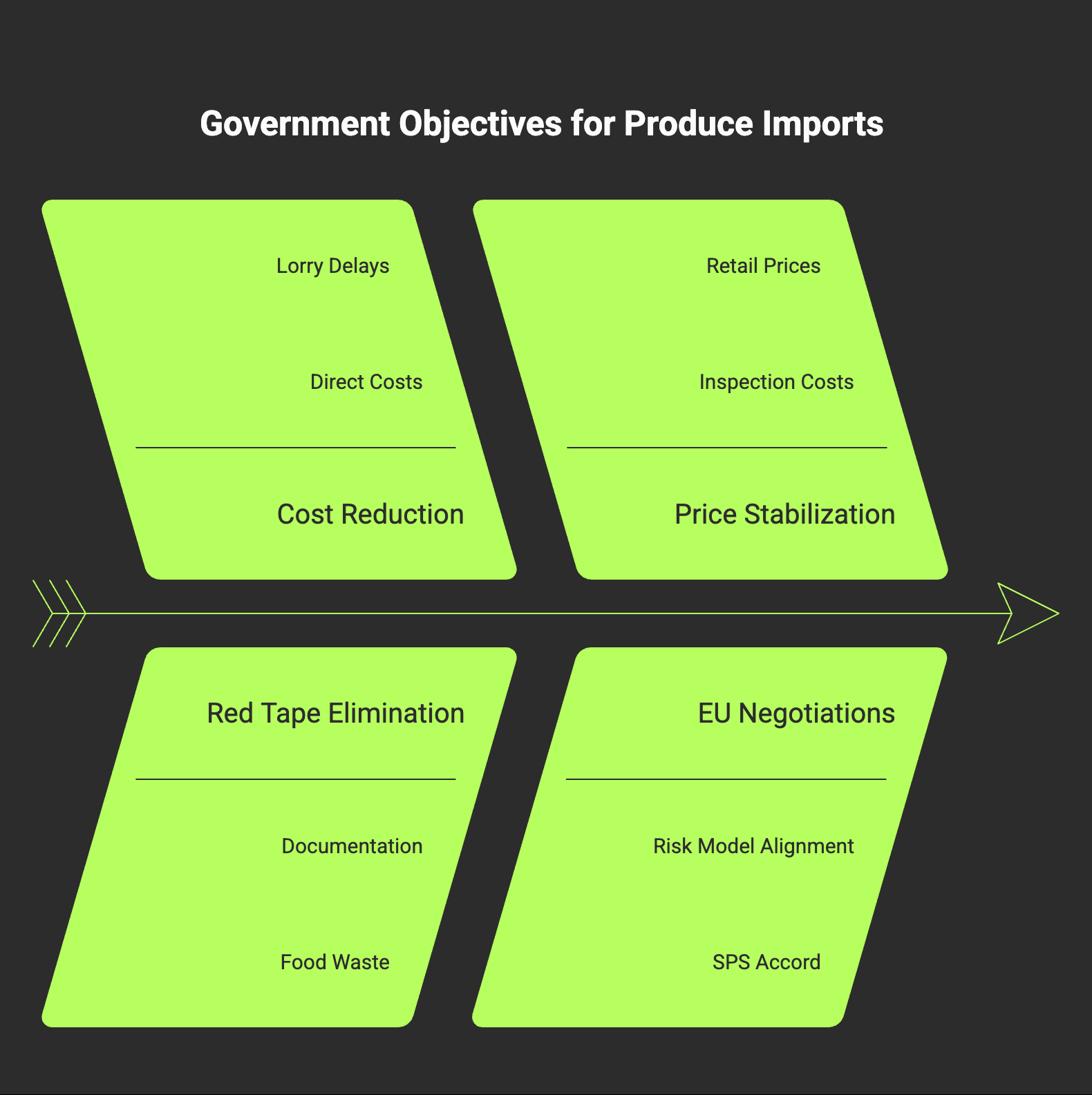

Government Rationale: Four Stated Objectives

Saving businesses time and money. DEFRA’s impact assessment put the direct cost of the new controls for produce importers at roughly £200 million per year once additional fees, lorry delays and spoilage were included. Eliminating those costs is expected to strengthen working-capital headroom in a sector characterised by tight margins and perishable inventory.

Avoiding unnecessary red tape. Fresh-produce supply chains rely on just-in-time cross-Channel flows. A single consignment of mixed salad may stop at four EU farms, two pack-houses and three UK distribution centres in twenty-four hours. Extra documentation fragments that network and increases food waste.

Easing pressure on food prices. With headline food inflation still running above historical norms, ministers argue that stripping out the marginal cost of inspections will help dampen retail prices for popular staples such as tomatoes and table grapes.

Creating negotiating space for an SPS accord with the EU. The suspension aligns the UK regime more closely with the EU’s own risk model and removes a potential irritant at a delicate moment in bilateral talks. Officials on both sides have hinted that a UK-EU “SPS zone”, modelled on existing EU accords with New Zealand and Switzerland, could be agreed within the next eighteen months.

Biosecurity: Are the Gates Now Wide Open?

DEFRA insists the answer is an emphatic no. The United Kingdom will continue to apply a risk-based surveillance model, meaning:

- Digital pre-notifications remain mandatory for high-risk or controlled plant material.

- Intelligence-led spot checks can be triggered at any time if pest outbreaks occur in the exporting member state.

- Pest-free-area requirements and emergency measures under existing Plant Health Regulations remain intact.

- Large commercial growers must still register with the UK Plant Health Service and are subject to domestic inspections.

The department argues that these layered controls provide “comparable or superior” protection to routine border checks, which often focus on paperwork rather than scientific risk.

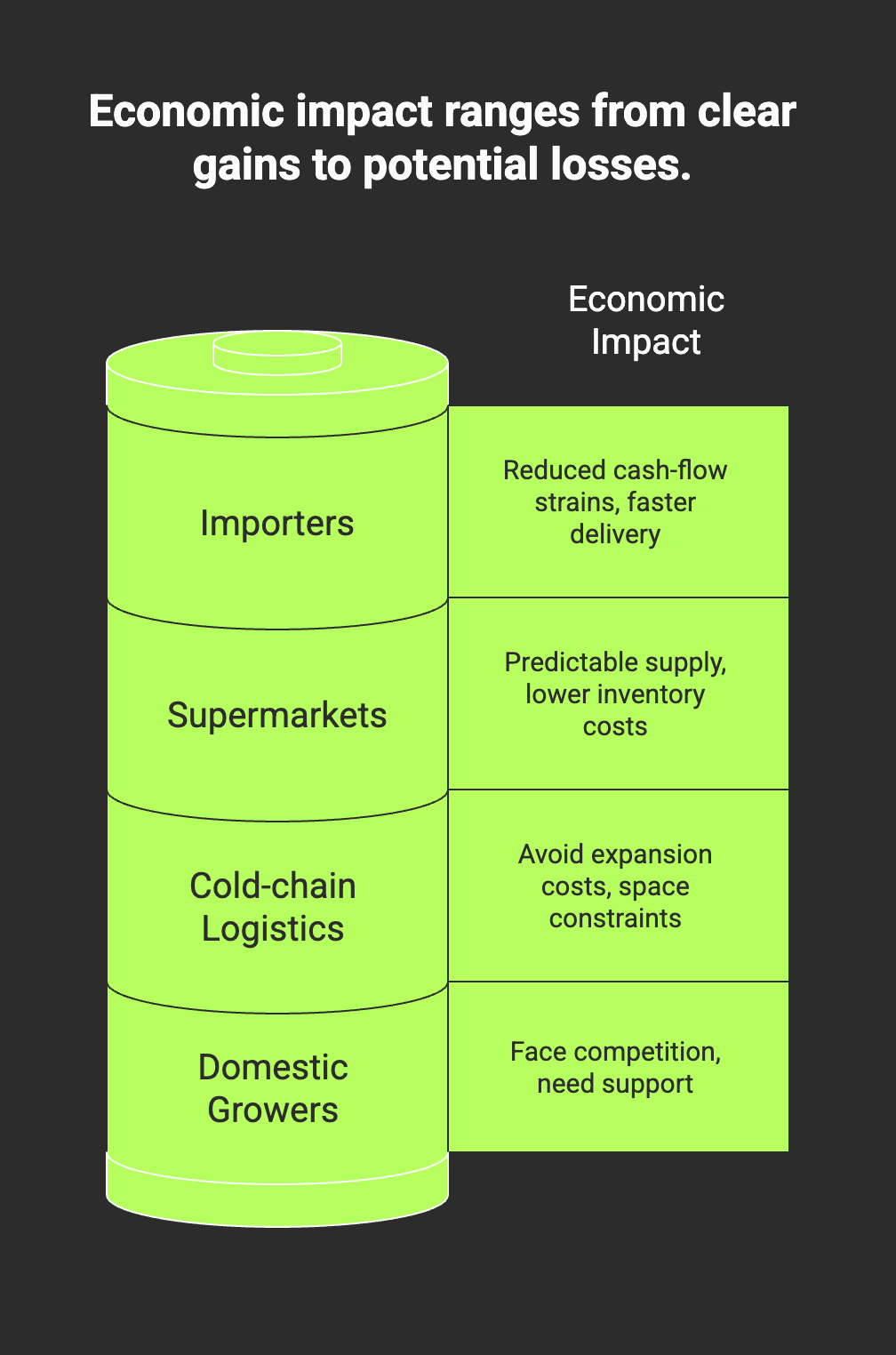

Economic Impact: Winners, Offsets and Grey Areas

Importers and wholesalers stand to gain first. The Fresh Produce Consortium (FPC), representing more than 700 produce businesses, welcomed the decision as “a rational, cost-of-living intervention”. Many members had budgeted for new cash-flow strains: an extra hour’s wait at Dover can destroy the shelf life of berries in summer heat.

Supermarkets and hospitality operators anticipate more predictable supply and inventory costs. Retail economists note that fruit and vegetables account for roughly 9 per cent of the UK grocery basket; even marginal savings can influence the official Consumer Prices Index.

Cold-chain logistics providers avoid capital expenditure on BCP expansions and extra staff. Dover, the busiest roll-on/roll-off port, recently warned MPs that space constraints made a July deadline “unworkable”.

Domestic growers are more ambivalent. While many rely on imported plugs, seeds and tunnel equipment, they also compete with European produce, particularly during shoulder seasons. National Farmers’ Union (NFU) representatives caution that “open-border asymmetry” could undermine investment in UK glasshouses unless mirrored by expanded labour-scheme quotas and energy-cost support.

Stakeholder Reactions in Detail

Fresh Produce Consortium – Applauds the extension, citing “common sense” and urging swift agreement on a permanent SPS chapter that eliminates double regulation.

British Retail Consortium – Notes that members will pass cost savings to consumers where possible, but stresses that currency movements and energy prices remain bigger drivers of retail pricing.

Horticultural Trades Association – Welcomes clarity but calls for equal attention to high-risk live-plant categories which still face full fees.

Port of Dover and Eurotunnel – Express relief; both operators had warned of queueing and refrigerated-unit congestion.

National Farmers’ Union – Seeks assurances that any UK-EU SPS deal will protect phytosanitary integrity and not erode domestic standards.

European Commission – Views the UK step as a constructive gesture that could accelerate talks but reminds exporters that full EU export-health certification rules continue to apply when shipping animal products in the opposite direction.

6 Frequently Asked Questions

Which products are affected by the postponement of SPS checks?

Only medium-risk fruit and vegetable imports from EU member states are covered. Fresh tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, citrus fruit, soft fruit, stone fruit and table grapes are the main lines. High-risk plants, seeds, meat, dairy and composite foods remain subject to existing controls.

Will consumers see cheaper fruit and vegetables immediately?

Wholesale prices should benefit almost at once from lower clearance costs and faster transit times. The degree to which this flows through to supermarket shelves depends on supply-chain contracts, fuel costs and seasonal yield fluctuations.

Is UK biosecurity compromised by relaxing physical inspections?

DEFRA says no: targeted surveillance, pest-alert rapid-response teams and importer registration schemes remain in force. The risk profile of EU-origin produce is judged low and traceability mechanisms are strong.

How does this decision interact with the forthcoming UK-EU SPS agreement?

Officials frame the easement as a “bridge” to a permanent accord that would align risk-assessment frameworks and remove most routine SPS checks in both directions, similar to the New Zealand-EU veterinary agreement.

Strategic Outlook: Beyond the Immediate Relief

The UK’s approach to border biosecurity has been iterative since 2020, marked by repeated extensions and technology pilots. By choosing a lengthy easement rather than another short delay, ministers appear to be signalling a pivot toward negotiated alignment instead of standalone enforcement. An SPS zone would likely:

- Replace physical inspections with electronic certification and remote auditing.

- Guarantee reciprocal market access for meat, dairy and live animals – sectors still saddled with costly veterinary bureaucracy.

- Tie dispute resolution to a scientific committee rather than a trade remedies panel, reducing the politicisation of health measures.

For traders, however, uncertainty persists. Investment in customs-broker training, BCP infrastructure and software integration has already been sunk. Businesses now face a strategic decision: maintain dual systems in anticipation of sudden policy shifts, or embed the easier regime and risk being caught unprepared in 2027.

Conclusion: A Breathing Space, Not a Full Stop

The United Kingdom’s decision to keep the door open to most EU fresh produce for another nineteen months brings palpable relief to importers, retailers and families juggling food bills. It also buys negotiators valuable time to craft a rational, scientifically grounded SPS partnership with the EU – one that could restore frictionless trade for the entire agri-food spectrum.

Yet this is not a permanent settlement. Businesses that use the reprieve to streamline documentation, digitise traceability, and invest in pest-prevention best practice will be best placed, whatever the regime that takes effect after January 2027. The policy may have changed, but the imperative of safe, swift and sustainable food supply chains remains exactly the same.